Dihydrogen cation

The hydrogen molecular ion, dihydrogen cation, or H2+, is the simplest molecular ion. It is composed of two positively-charged protons and one negatively-charged electron, and can be formed from ionization of a neutral hydrogen molecule. It is of great historical and theoretical interest because, having only one electron, the Schrödinger equation for the system can be solved in a relatively straightforward way due to the lack of electron–electron repulsion (electron correlation). The analytical solutions for the energy eigenvalues are a generalization of the Lambert W function (see Lambert W function and references therein for more details on this function).[1] Thus, the case of clamped nuclei can be completely done analytically using a Computer algebra system. Consequently, it is included as an example in most quantum chemistry textbooks.

The first successful quantum mechanical treatment of H2+ was published by the Danish physicist Øyvind Burrau in 1927,[2] just one year after the publication of wave mechanics by Erwin Schrödinger. Earlier attempts using the old quantum theory had been published in 1922 by Karel Niessen[3] and Wolfgang Pauli,[4] and in 1925 by Harold Urey.[5] In 1928, Linus Pauling published a review putting together the work of Burrau with the work of Walter Heitler and Fritz London on the hydrogen molecule.[6]

Bonding in H2+ can be described as a covalent one-electron bond, which has a formal bond order of one half.[7]

The ion is commonly formed in molecular clouds in space, and is important in the chemistry of the interstellar medium.

Contents |

Quantum mechanical treatment, symmetries, and asymptotics

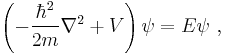

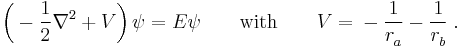

The simplest electronic Schrödinger wave equation for the hydrogen molecular ion  is modeled with two fixed nuclear centers, labeled A and B, and one electron. It can be written as

is modeled with two fixed nuclear centers, labeled A and B, and one electron. It can be written as

where  is the electron-nuclear Coulomb potential energy function:

is the electron-nuclear Coulomb potential energy function:

and E is the (electronic) energy of a given quantum mechanical state (eigenstate), with the electronic state function  depending on the spatial coordinates of the electron. An additive term

depending on the spatial coordinates of the electron. An additive term  , which is constant for fixed inter-nuclear distance

, which is constant for fixed inter-nuclear distance  , has been omitted from the potential

, has been omitted from the potential  , since it merely shifts the eigenvalue. The distances between the electron and the nuclei are denoted

, since it merely shifts the eigenvalue. The distances between the electron and the nuclei are denoted  and

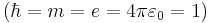

and  . In atomic units

. In atomic units  the wave equation is

the wave equation is

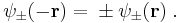

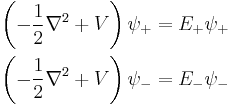

We can choose the midpoint between the nuclei as the origin of coordinates. It follows from general symmetry principles that the wave functions can be characterized by their symmetry behavior with respect to space inversion (r  -r). There are wave functions :

-r). There are wave functions : , which are symmetric with respect to space inversion, and there are wave functions :

, which are symmetric with respect to space inversion, and there are wave functions : , which are anti-symmetric under this symmetry operation:

, which are anti-symmetric under this symmetry operation:  We note that the permutation (exchange) of the nuclei has a similar effect on the electronic wave function. We only mention that for a many-electron system proper behavior of

We note that the permutation (exchange) of the nuclei has a similar effect on the electronic wave function. We only mention that for a many-electron system proper behavior of  with respect to the permutational symmetry of the electrons (Pauli exclusion principle) must be guaranteed, in addition to those symmetries just discussed above. Now the Schrödinger equations for these symmetry-adapted wave functions are

with respect to the permutational symmetry of the electrons (Pauli exclusion principle) must be guaranteed, in addition to those symmetries just discussed above. Now the Schrödinger equations for these symmetry-adapted wave functions are

The ground state (the lowest discrete state) of  is the

is the  state [8] with the corresponding wave function

state [8] with the corresponding wave function  denoted as

denoted as  . There is also the first excited

. There is also the first excited  state, with its

state, with its  labeled as

labeled as  . (The suffixes g and u are from the German gerade and ungerade) occurring here denote just the symmetry behavior under space inversion. Their use is standard practice for the designation of electronic states of diatomic molecules, whereas for atomic states the terms even and odd are used. Asymptotically, the (total) eigenenergies

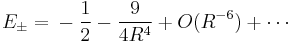

. (The suffixes g and u are from the German gerade and ungerade) occurring here denote just the symmetry behavior under space inversion. Their use is standard practice for the designation of electronic states of diatomic molecules, whereas for atomic states the terms even and odd are used. Asymptotically, the (total) eigenenergies  for these two lowest lying states have the same asymptotic expansion in inverse powers of the inter-nuclear distance R [9]:

for these two lowest lying states have the same asymptotic expansion in inverse powers of the inter-nuclear distance R [9]:

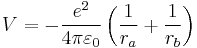

The actual difference between these two energies is called the exchange energy splitting and is given by [10]:

which exponentially vanishes as the inter-nuclear distance R gets greater. The lead term  was first obtained by the Holstein–Herring method. Similarly, asympotic expansions in powers of 1/R have been obtained to high order by Cizek et al. for the lowest ten discrete states of the hydrogen molecular ion (clamped nuclei case). For general diatomic and polyatomic molecular systems, the exchange energy is thus very elusive to calculate at large inter-nuclear distances but is nonetheless needed for long-range interactions including studies related to magnetism and charge exchange effects. These are of particular importance in stellar and atmospheric physics.

was first obtained by the Holstein–Herring method. Similarly, asympotic expansions in powers of 1/R have been obtained to high order by Cizek et al. for the lowest ten discrete states of the hydrogen molecular ion (clamped nuclei case). For general diatomic and polyatomic molecular systems, the exchange energy is thus very elusive to calculate at large inter-nuclear distances but is nonetheless needed for long-range interactions including studies related to magnetism and charge exchange effects. These are of particular importance in stellar and atmospheric physics.

The energies for the lowest discrete states are shown in the graph above. These can be obtained to within arbitrary accuracy using computer algebra from the generalized Lambert W function (see eq.  in that site and the reference of Scott, Aubert-Frécon, and Grotendorst) but were obtained initially by numerical means to within double precision by the most precise program available, namely ODKIL.[11] The red full lines are

in that site and the reference of Scott, Aubert-Frécon, and Grotendorst) but were obtained initially by numerical means to within double precision by the most precise program available, namely ODKIL.[11] The red full lines are  states. The green dashed lines are

states. The green dashed lines are  states. The blue dashed line is a

states. The blue dashed line is a  state and the pink dotted line is a

state and the pink dotted line is a  state. Note that although the generalized Lambert W function eigenvalue solutions supersede these asymptotic expansions, in practice, they are most useful near the bond length. These solutions are possible because the partial differential equation of the wave equation here separates into two coupled ordinary differential equations using prolate spheroidal coordinates.

state. Note that although the generalized Lambert W function eigenvalue solutions supersede these asymptotic expansions, in practice, they are most useful near the bond length. These solutions are possible because the partial differential equation of the wave equation here separates into two coupled ordinary differential equations using prolate spheroidal coordinates.

Formation

The dihydrogen ion is formed in nature by the interaction of cosmic rays and the hydrogen molecule. An electron is knocked off leaving the cation behind.[12]

- H2 + cosmic ray → H2+ + e- + cosmic ray.

Cosmic ray particles have enough energy to ionize many molecules before coming to a stop.

In nature the ion is destroyed by reacting with other hydrogen molecules:

- H2+ + H2 → H3+ + H.

The ionization energy of the hydrogen molecule is 15.603 eV. The dissociation energy of the ion is 1.8 eV. High speed electrons also cause ionization of hydrogen molecules. The peak cross section for ionization for high speed protons is 70000 eV with a cross section of 2.5x10−16 cm2. A cosmic ray proton at lower energy can also strip an electron off a neutral hydrogen molecule to form a neutral hydrogen atom, with a peak cross section at around 8000 eV of 8x10−16 cm2.[13]

An artificial plasma discharge cell can also produce the ion.

See also

- Dirac Delta function model ( 1-D version of H2+)

- Di-positronium

- Euler's three-body problem (classical counterpart)

- Few-body systems

- Trihydrogen cation

- Triatomic hydrogen

- Lambert W function

- Molecular astrophysics

- Holstein–Herring method

- Three-body problem

References

- ^ Scott, T. C.; Aubert-Frécon, M.; Grotendorst, J. (2006). "New Approach for the Electronic Energies of the Hydrogen Molecular Ion". Chem. Phys. 324 (2–3): 323–338. arXiv:physics/0607081. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2005.10.031.

- ^ Burrau Ø (1927). "Berechnung des Energiewertes des Wasserstoffmolekel-Ions (H2+) im Normalzustand." (in German). Danske Vidensk. Selskab. Math.-fys. Meddel. M 7:14: 1–18. http://www.royalacademy.dk/CatalogEntry.asp?id=862.

Burrau Ø (1927). "The calculation of the Energy value of Hydrogen molecule ions (H2+) in their normal position" (in German) (PDF). Naturwissenschaften 15 (1): 16–7. doi:10.1007/BF01504875. http://www.springerlink.com/content/h60148l4717uv805/fulltext.pdf. - ^ Karel F. Niessen Zur Quantentheorie des Wasserstoffmolekülions, doctoral dissertation, University of Utrecht, Utrecht: I. Van Druten (1922) as cited in Mehra, Volume 5, Part 2, 2001, p. 932.

- ^ Pauli W (1922). "Über das Modell des Wasserstoffmolekülions". Ann. D. Phys. 373 (11): 177–240. doi:10.1002/andp.19223731101. Extended doctoral dissertation; received 4 March 1922, published in issue No. 11 of 3 August 1922.

- ^ Urey HC (October 1925). "The Structure of the Hydrogen Molecule Ion". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 11 (10): 618–21. doi:10.1073/pnas.11.10.618. PMC 1086173. PMID 16587051. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1086173.

- ^ Pauling, L. (1928). "The Application of the Quantum Mechanics to the Structure of the Hydrogen Molecule and Hydrogen Molecule-Ion and to Related Problems". Chemical Reviews 5 (2): 173–213. doi:10.1021/cr60018a003.

- ^ Clark R. Landis; Frank Weinhold (2005). Valency and bonding: a natural bond orbital donor-acceptor perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–100. ISBN 0-521-83128-8.

- ^ Huber, K.-P.; Herzberg, G. (1979). Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure. IV. Constants of Diatomic Molecules. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- ^ Čížek, J.; Damburg, R. J.; Graffi, S.; Grecchi, V.; Harrel II, E. M.; Harris, J. G.; Nakai, S.; Paldus, J. et al. (1986). "1/R expansion for H2+: Calculation of exponentially small terms and asymptotics". Phys. Rev. A 33: 12–54. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.33.12.

- ^ Scott, T. C.; Dalgarno, A.; Morgan III, J. D. (1991). "Exchange Energy of H2+ Calculated from Polarization Perturbation Theory and the Holstein-Herring Method". Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 (11): 1419–1422. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.1419.

- ^ Hadinger, G.; Aubert-Frécon, M.; Hadinger, G. (1989). "The Killingbeck method for the one-electron two-centre problem". J. Phys. B 22 (5): 697–712. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/22/5/003.

- ^ Herbst, E. (2000). "The Astrochemistry of H3+". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A. 358 (1774): 2523–2534. doi:10.1098/rsta.2000.0665.

- ^ Padovani, Marco; Galli, Daniele; Glassgold, Alfred E. (2009). "Cosmic-ray ionization of molecular clouds". Preprint. arXiv:0904.4149.

![\Delta E = E_{-} - E_{%2B} = \frac{4}{e} \, R \, e^{-R} \left[ \, 1 %2B \frac{1}{2R} %2B O(R^{-2}) \, \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cfae35f9a01fc1537678b3fe1b51cd8c.png)